Jupiter's moons

On 7 January 1610, Galileo observed with his telescope what he described at the time as "three fixed stars, totally invisible[b] by their smallness", all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it.[52] Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these "stars" relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January, Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days, he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter: he had discovered three of Jupiter's four largest moons.[53] He discovered the fourth on 13 January. Galileo named the group of four the Medicean stars, in honour of his future patron, Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Cosimo's three brothers.[54] Later astronomers, however, renamed them Galilean satellites in honour of their discoverer. These satellites were independently discovered by Simon Marius on 8 January 1610 and are now called Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, the names given by Marius in his Mundus Iovialis published in 1614.[55]

Galileo's observations of the satellites of Jupiter caused controversy in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth,[56][57] and many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing.[58][59] Compounding this problem, other astronomers had difficulty confirming Galileo's observations. When he demonstrated the telescope in Bologna, the attendees struggled to see the moons. One of them, Martin Horky, noted that some fixed stars, such as Spica Virginis, appeared double through the telescope. He took this as evidence that the instrument was deceptive when viewing the heavens, casting doubt on the existence of the moons.[60][61] Christopher Clavius's observatory in Rome confirmed the observations and, although unsure how to interpret them, gave Galileo a hero's welcome when he visited the next year.[62] Galileo continued to observe the satellites over the next eighteen months, and by mid-1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their periods—a feat which Johannes Kepler had believed impossible.[63][64]

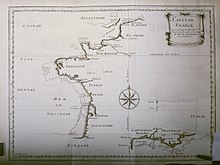

Galileo saw a practical use for his discovery. Determining the east–west position of ships at sea required their clocks to be synchronized with clocks at the prime meridian. Solving this longitude problem had great importance to safe navigation and large prizes were established by Spain and later Holland for its solution. Since eclipses of the moons he discovered were relatively frequent and their times could be predicted with great accuracy, they could be used to set shipboard clocks and Galileo applied for the prizes. Observing the moons from a ship proved too difficult, but the method was used for land surveys, including the remapping of France.[65]: 15–16 [66]